Interview with Timothy McCormack

Zach Sheets

February 2019

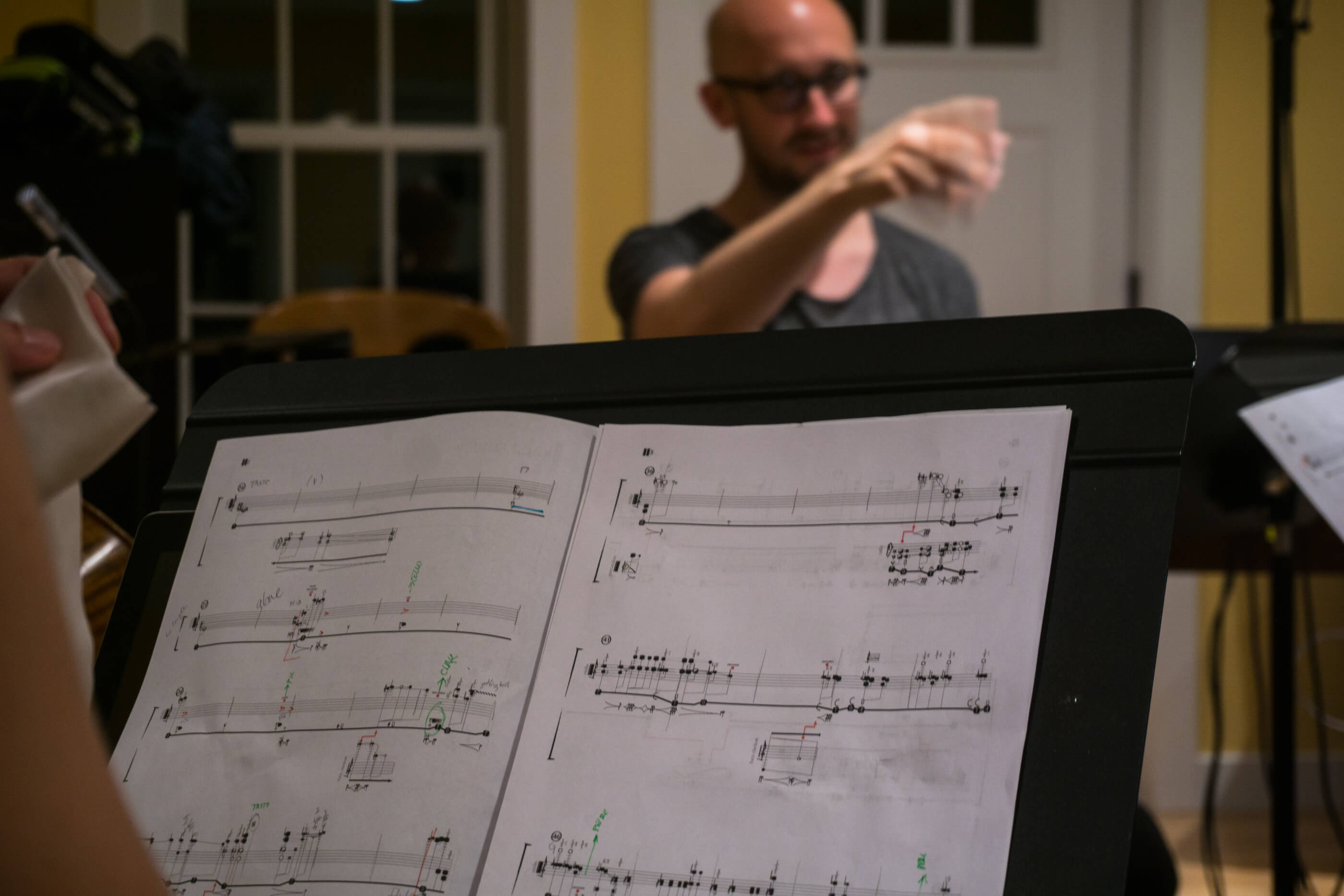

Before our upcoming concert, I sat down with composer Tim McCormack, whose work–and [Switch~ Ensemble] commission–karst survey will see its US premiere in [Switch~]’s February 28th show at Areté Gallery and Venue. We talked about new and old projects, their inspirations, how to work with musicians, and what makes music vivid for Tim.

Tim McCormack: Well, hello.

Zach Sheets: Thanks so much for joining me, Tim.

TM: It’s so nice to see you, Zach.

ZS: I feel like we’re doing a podcast.

TM: Right?

ZS: Well… perhaps you could start by sharing who you are and what you’re up to?

TM: Sure. My name is Tim McCormack. I’m from Cleveland, Ohio, the youngest of four children. I do not come from a musical family, but I grew up learning lots of instruments, the last of which somehow became my main instrument: the bassoon. I think that learning the bassoon really informed how I approach all other instruments, which is that I’m always thinking of the instrument’s mechanism and our physical relationship to it. The left thumb of a bassoon player controls about 11 keys, so as a bassoonist, you’re always negotiating this really complex mechanism. That informed how I think about all instruments as a composer.

I stayed in Ohio for my undergrad, then moved to Chicago and got to know the new music scene there. Then I did two years in England, studying, moved back to Chicago, and now to Boston in 2011.

ZS: You mentioned you’re in the middle of finishing up a couple of projects. Can you share what they are, yet?

TM: Oh, yeah! The thing that is literally on my desk right now is actually an old project. I am finishing a string quartet I wrote and that was quote-unquote premiered…

ZS: Tim is making airquotes, for those….

TM: Well, I didn’t quote-unquote write it

ZS: …for those podcast listeners at home.

TM: We’re going to talk for an hour and 90% is going to be unusable, isn’t it?

ZS: [laughs]

TM: Anyway, right now I’m finishing a string quartet called your body is a volume, which I started writing at the tail end of 2016. In the past 3 or 4 years most of my pieces take place on these really extended time scales—mostly 30 to 60 minutes - but the festival that commissioned the piece couldn’t commit to such a long duration. As I was writing the piece, I realized it was a really important one for me, and I that I couldn’t skim it. So, in the end, we premiered the second half of the piece, which was 30 minutes, and the piece all-in-all will be at least 60.

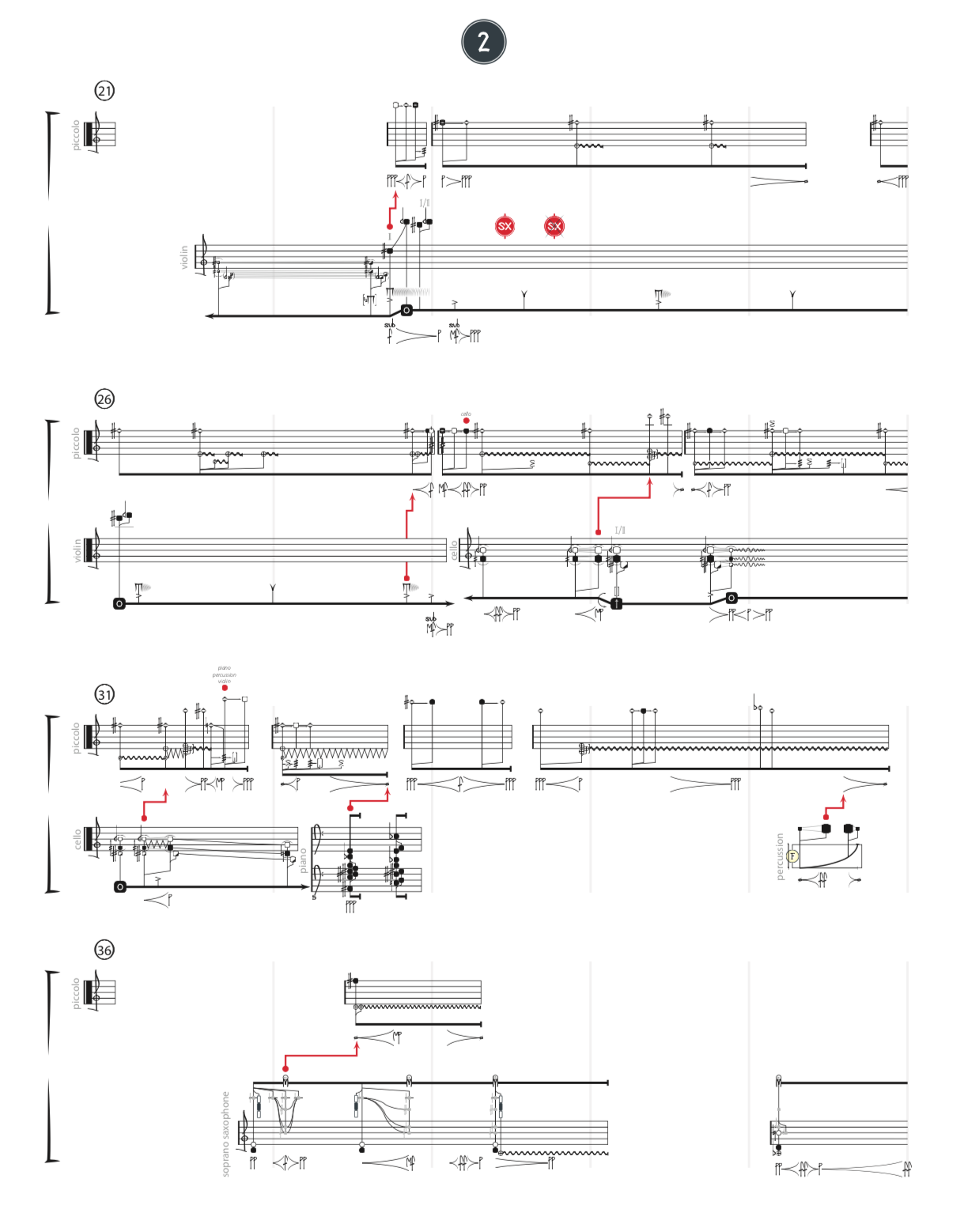

As far as new projects are concerned, for the past 5-6 years I’ve been working on a big project with Australia’s ELISION Ensemble and Line Upon Line percussion trio (Austin, TX). The three of us are collaborating on a work titled KILN, which I’m calling a kind of concert installation, with a dispersal of musicians throughout the space. It will probably be 80 minutes of uninterrupted music for 10 musicians, But, it’s also comprised of 5 smaller chamber pieces: a percussion solo, a percussion trio, and three mixed trios.

I’m also working on some new works for Curious Chamber Players, following an old collaboration with Faint Noise: Karin Hellqvist, Anna Petrini, and Malin Bång. One of them is a solo piece for Anna Petrini, a Paetzold contrabass recorder player. The other is quite a different work for solo contrabass recorder with ensemble.

Dance, Physicality, and Music

ZS: So, I’d love to go back to something you were talking about at the very beginning, which is your relationship to instrumental mechanism and physicality. You’re very interested in dance—and you dance, yourself, right?

TM: I haven’t actually danced publicly at this point for a number of years, but yes. Basically, I had been studying dance “academically” because of its relevance to my own compositional project, and I got to a point where I realized that if I really wanted to understand why dance is so significant for me—musically or compositionally—I would need to do it. And, that was the first year in my PhD program at Harvard, which also happened to be the year that Jill Johnson was named director of the the university’s dance department.

ZS: Who happened to be a Forsythe dancer.

TM: Who happened to be a dancer from the very company that all of my research was about. When I say that dance is significant for me, it really is the work of William Forsythe and his company that’s most relevant to my compositional project. So, I took dance classes, and I think because I had been studying their technique from a distance for so many years, it was lying dormant in my body. Once I was actually doing it, it came really naturally to me. It was feeding and energizing my own compositional work—but it also became its own independent thing.

ZS: I’m curious both about the history and about right now when it comes to a few aspects of your musical thinking. I’m trying to find a way to wrangle this question… it’s sort of like, summarize your entire aesthetic position, which is not a very good question.

TM: Well, I have to do that in a couple months when I give my dissertation colloquium, so this is good practice.

ZS: In that case: in a daily practice of composing, how do you find that these questions of physical technique—either the gravity of dancing or the instrumental technique of how a tongue connects to a reed, fingers to keys—how do they affect your thinking? Is it in a very practical way, in a very direct way where you’re thinking about sound? Or is it also a philosophical aesthetic position?

TM: I think it’s both, at this point. A few years ago, I was thinking very one-to-one, surface-level relationship between dance and music-making—in that they’re both physical, they’re both bodily, and corporal. That’s still there, but it has seeped into this deeper, more substantial place.

Put it this way: I came to dance because my music was extremely physical. By which I mean, highly gestural, requiring a certain relationship between the body and the instrument that is very physical.

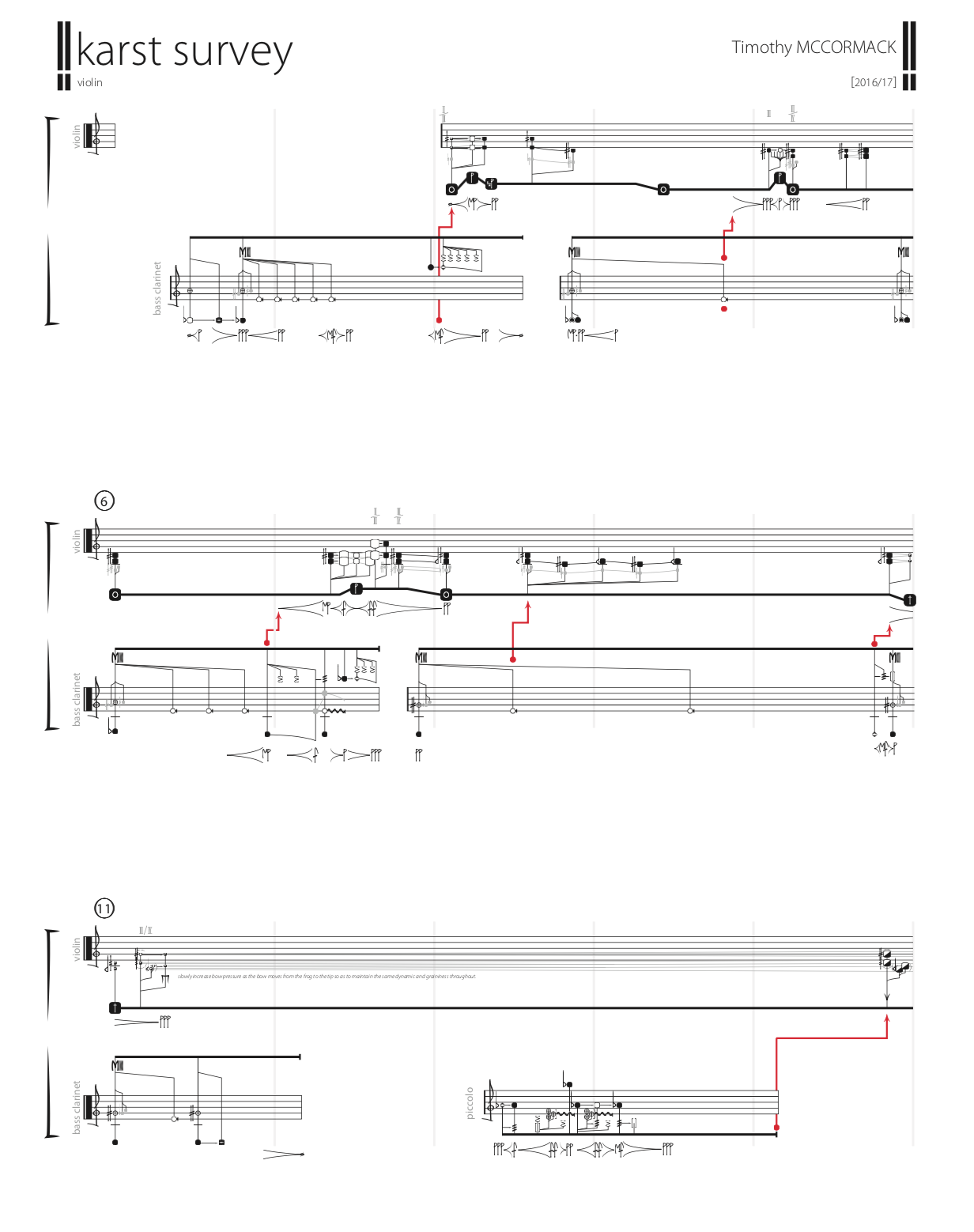

ZS: Like your notation, which describes the action of the player?

TM: Yeah, notating the action of the player, and the sound follows from that. That’s why I initially came to dance. But then, having this experience within dance has inverted that physicality in my music. Now, the physicality that was the shimmering surface of my music has been so much more deeply embedded into the music, such that it’s not this wild display of physical gesture. It’s a much more internal thing. The way that I’ve been thinking about it is that over the past however-many years my music has gone from being an enactment of physicality to an embodiment of the physicality.

WORLDEATER requires really fine control over physical action, like embouchure control. But the range of movement is so delimited, because the actual sounds that are being aimed for are so much more specific. The physicality is pointed toward the sound instead of the sound springing from the physicality.

Composers and Performers

ZS: So, I’m wondering if you can talk about the process of editing—either while the work is in progress on the desk, or as you work with performers in rehearsal. We think of composers as imagining a sounding result, then working with the players to find the right technique. But, in your music, it’s often the opposite. Do you have times where someone does the right technique but the sound is wildly off? And how do you work with players when it’s not aligning, and when the sound is not the right thing?

TM: Well, despite the fact that I prescribe physical movement, whether it’s through tablature or some sort of hybrid notation, I’ve always known the sound I want. It’s not imagined: it’s arrived-at through my own experimentation with the instrument, or working together with the musician I’m writing for. I try to understand the sound and the physicality as fully as I can before I start writing for it. I really feel uncomfortable when I don’t fully understand how a sound is made, or I don’t fully know what the sound is that I want. I need to know the realities.

ZS: Do you find that becoming more true, as you mentioned your shift away from this behemoth, external virtuosity, toward a bit more inward-facing kind?

TM: Definitely: it has definitely become more true in recent years. In earlier pieces, the range of sonic results were more broad. Now, today, in the stuff that I’m writing all the sounds are really specific. They have to be “this” or “that,” but I still think of them in terms of how they’re being made and I try to notate that.

As far as working with musicians—every musician has different ways they think about their instrument and music-making. Some people are really open and really flexible; some people trust you and some people don’t. What I’m learning about myself is that my ability to guide someone through these techniques really depends on their openness—their trust in me, basically.

My trust in a performer is very dependent on their trust in me. In general I have really positive experiences with musicians and ensembles who are learning my music.

ZS: I think you do a good job of cultivating a kind of understated confidence. I remember working with you on some of the double trills in karst survey. I came in, saying the keywork on my piccolo is particularly narrow and my fingers are kind of fat, I’m just not sure it will work, etc. And you were like “yeah… you can do it.”

TM: [laughs]

ZS: It didn’t feel confrontational, just assertive. Like, no no, I’ve worked this out. It’s going work, you can trust me. Now, my fingers are still awfully fat and it’s very hard, but…

TM: [laughs] That’s the thing…

ZS: Did you practice cultivating that persona?

TM: I don’t know, I think that’s just me, when I feel comfortable with the person I’m working with. I am confident in myself because I know that I’ve put in the work. I’ve gotten my hands on an instrument; I’ve worked with musicians; I’ve taken the time to understand what I’m writing, and I know why it needs to be like that.

When it’s two people just trying to figure out something together, I feel like it’s my job as a composer to encourage them—that they can do this. Not only because I know that it’s possible, but also because it’s cool. These things are cool. And maybe you’ll find it cool, too.

I’m not saying that it’s not challenging. But I have had experiences where the fact that it is challenging is misconstrued as “it’s impossible and the composer doesn’t know what he’s doing.” When I’m confronted with that, it’s really hard for me to hear you telling me anything other than you’re not going to do it. At that point, I don’t know what I can do to make you change your mind, because you’ve already made up your mind.

ZS: I’m curious to talk more about karst survey, which might be my favorite piece of yours.

TM: Thanks. It’s one of my favorite pieces of mine, too.

About Karst Survey

ZS: I was writing recently about [Switch~]’s tour from 2016 and about karst survey’s threadbare lyricism, which I think is so beautiful and so striking. It’s interesting to me that there’s this incongruity with the content of the music—that’s so carefully etched and every detail fits just in its right place—and the container of the entire piece, which has this giant monolith in the latter two-thirds that is the most abrupt thing you could imagine.

TM: Yeah. One of the reasons why I love this piece is because I felt like I was really taking different types of risks than I usually take. Another reason why I love this piece is because I feel like it was the first piece where I attained what I think you’re calling this really fine lyricism—which was something I had been trying to achieve for a long time.

karst survey is what it is because of the piece I wrote just before it, called KARST. The two pieces are really different, but share a lot of genetic makeup: it’s difficult to talk about karst survey’s coming-into-being without talking about KARST. The central metaphor was a karst, which is a particular type of geologic landscape. There’s a lot going on in them, because of the particular type of limestone involved. There are complex cave systems, rivers disappearing into caves, underground lakes, streams that hop above ground again, sinkholes, and so on. It’s a very eroded terrain, both inside and out.

My hope when I wrote KARST was to feel like you’re in this eroded sonic landscape, and that the features of the piece keep suddenly changing. When I finished KARST, before I heard the piece, I felt like I failed at that. It was more like we’re in a helicopter above the landscape, and we see all the connections. We see how the sink hole is funneling this lake into the cave. We see it all, but I wanted us to not see it: I wanted us to experience it—to be walking through this weathered terrain and then suddenly fall in a sinkhole to a lake underground, or whatever.

So, writing karst survey: it’s a survey—a geologic survey of the landscape, where I really wanted to put the listener on the ground walking through it and not understanding the connections between its features. After the first nine minutes of this refined lyricism and tightly-knit contrapuntal ensemble activity, there are these abrupt changes that happen. I was thinking very intentionally about the durations of them.

I wanted each section to establish itself immediately, so that the listener feels they can see into the future of a certain material—but then 5-10 seconds later, that future is obliterated, and we’re in this completely other zone. The most extreme example being the introduction of the electronics, which is this noise wall that happens for a long time. Once it leaves, we’re back in that really fine lyricism from the beginning—but that only lasts for about 30 seconds and then the piece is done.

I wanted it to be surprising in its form, but also have a sort of logic of a world that was built. I wanted to put the listener really in the middle of this landscape, and you’re only seeing what you’re able to see—you don’t see how they whole thing connects until you’ve walked through it all.

ZS: Did you have reservations about this electronics aspect of it–that it was going to work well? Because, all other things being equal, the idea of a new music piece that’s very quiet for the first half and then starts increasingly changing pace, and then 2/3 of the way through goes bananas, and has a quiet one-minute coda… there’s a lot of cliché pitfalls there–which I think you avoided. Were you nervous you were going to land in any of them?

TM: No, actually. I think I had just blind confidence in myself [laughs], throughout the process. I knew this move–the really loud section–is dropped into what is largely a quiet and delicate piece. I just had this belief that I knew why it was there; I knew the function of it. It’s surprising, but I don’t think it comes off as antagonistic towards a listener. I don’t think it reduces itself to being “about” this extreme move; it contributes to some larger thing the piece has built.

Part of the reason is that I think there is actually a bit of a “step up” to it, with the piano and percussion. In comparison to what came before, they have this really loud, suddenly noisy, turbulent moment. We only hear this for maybe 20 seconds before the electronics come in, but there is a sonic connection.

On Music-Making

ZS: So, in keeping with our podcast theme, may I ask a parting question?

TM: Sure.

ZS: I think your music is a fascinating thing for performers to engage with, because it draws on tradition in a unique way but also draws on so many other things in unique ways. It interrogates a lot of what we do as musicians. But, I’m also curious how you talk about your music with non-musicians. Your husband Tom is not a musician, like my partner Brittney. You’ll be at the show, so if you were to tell someone like Tom or Brittney at the door what you do or what’s important to you, how would you do it?

TM: I have different ways that I do it. Depends on my mood…[laughs] I’ve joked that it’s invisible fart music or a bunch of cutlery in a blender set to puree… those are somehow my go-to when I’m not in a good mood.

ZS: [laughs] When you’re, say, in line at the RMV.

TM: Right. But, seriously, the way I’ve been describing it to people who might not have an existing relationship with music like mine is that it’s like noise music or drone music, but played on orchestral instruments. That only goes so far into actually describing it, but it gives some sort of touchstone within a context they might have an idea about—and is a frame through which I’m comfortable with them listening to my music.

I will say I do think about how people listen to my music, and what I want them to experience or feel within it. I try to write music that provides some sort of invitation inside itself to a listener—no matter who they are. I feel like my music has become more and more personal and more and more… emotional in the past years. It’s being written more from my heart now than ever, and I feel like that is allowing me to communicate something to a listener that doesn’t depend on them having knowledge or experience or training in this type of music.

I believe that there is something that’s being communicated that is human, or heart-to-heart. That’s something that has become more important to me. When I say that I think about my listeners, or think about an audience, that doesn’t necessarily mean that I’m changing my work to make something more easily palatable. But I want there to be an invitation into it, and I would like for a listener of my music to feel like there’s something they themselves can take with them and unearth within that experience.

ZS: Tim, thank you so much. This has been a pleasure.

To buy tickets to [Switch~ Ensemble]’s concert on February 28 at Areté gallery, please visit: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/switch-ensemble-arete-tickets-54896909133

To read more about Tim McCormack, please visit: http://www.timothy-mccormack.com